How official “historians” conceal key facts – The Russian Revolution as a case in point

Mon 11:24 am +00:00, 16 Feb 2026

For a deeper dive down the rabbit hole see here:

Vladimir Lenin is Another Fake

https://mileswmathis.com/lenin.pdf

——————————–

There are many facts and sources that are not included in the conventional history books. This is particularly true of ground-breaking events that influence the world as a whole. Serious seekers should aim to uncover the causes of events, as these are often hidden, deliberately blurred or dismissed by those who record history.

Even in our very recent past, our present human civilisation does not have an objective overview and rational assessment of what really happened.

This presentation aims to highlight some essential facts and events that are unfortunately missing from mainstream history. Hopefully, they will help us to perceive the truth better.

Sometimes, an attempt has been made to differentiate between the ‘February Revolution of 1917’, also known as the ‘Kerensky Revolution’, and the ‘October Revolution of 1917’, which saw the definitive establishment of communism in Russia. Though distinct in time, these two events represent two phases of the same historical phenomenon, and distinguishing between them demonstrates a tragic and vexing lack of realistic appreciation. It is hoped that this misconception can be dispelled, as the unity and continuity of the revolutionary movement, and especially of the revolution itself, cannot be overstated.[1]

The 1917 revolutions enabled Bolshevism to seize power in Russia. Bolshevism was an offspiring of Marxist communism, a destructive doctrine that was publicised in the mid-19th century. The origins of this ideology are lesser known, yet essential to understanding the events of the 20th century, including the communist coup d’état of 1917. More details are given in an analysis The Origins of Communism and Socialism.

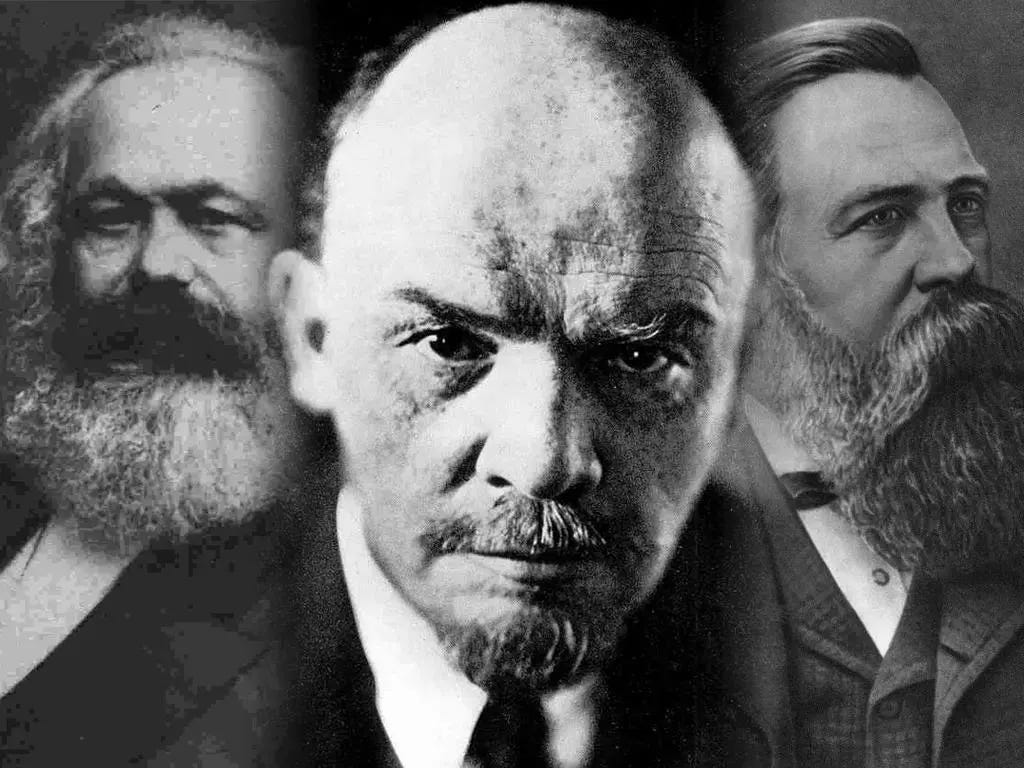

Karl Marx (along with Friedrich Engels) is widely regarded as the founder of international communism, having been tasked with writing the Communist Manifesto in 1848. However, the people behind Marx played a more significant role in designing the inhumane doctrine.

Moritz Moses Hess (1812–1875) had a considerable influence on both Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. In the early 1840s, Hess introduced Engels, the future famous communist, to communism and also introduced him to Marx. He has been called a communist rabbi and the father of modern socialism.[2] Due to his tireless efforts on behalf of revolutionary ideals, he earned the title of the ‘father of German communism’.[3]

Many statements made by Marxists, for example in their Manifesto, closely resemble those of Moses Hess. He advocated the elimination of matrimonial bondage and the replacement of the family by the state, as well as the education of young people.[4] It has been suggested that he introduced the idea of the abolition of private property, which was later adopted by Marx and Engels and became a cornerstone of communism in The Communist Manifesto.[5]

In 1847, Hess published an essay entitled Die Folgen der Revolution des Proletariats (The Consequences of the Proletarian Revolution), which contained many ideas that were formulated into the Communist Manifesto in 1848. These ideas included the struggle of the proletariat against an arch enemy and the use of relevant means.

Hess also introduced Marx and Engels to international Freemasonry. It has been claimed that Marx became a member of the Le Socialiste lodge in Brussels in 1845[6]

, and that he and Engels were freemasons of the 31st degree.[7]

Notably, the Belgian Masonic lodge Le Socialiste, which initiated Marx into Freemasonry, formulated a socialist plan to overthrow ruling regimes. On 5 July 1843, the lodge submitted a draft of this revolutionary plan of action, which was remarkably similar to The Communist Manifesto, published five years later in 1848. Bulletin du Grand Orient (June 1843) stated that this program was accepted by the Belgium’s largest masonic authority, Le Supreme Conseil de Belgique and that it was:

corresponding to the masonic doctrine concerning the social question and that the world which is united in Grand Orient should with all conceivable means aim to realise it.

Historian Nesta Webster has highlighted that the main core of the communist doctrine was formulated by Adam Weishaupt already in 1776, when the secret organisation Illuminati was formed:

In the Communist Manifesto … are set forth the doctrines laid down in the code of Weishaupt[8] – the abolition of inheritance, of marriage and the family, of patriotism, of all religion, the institution of the community of women, and the communal education of children by the State. This, divested of its trappings, is the real plan of Marxian Socialism…[9]

Winston Churchill praised Mrs Webster’s ability to make important revelations, claiming that there was a worldwide conspiracy to overthrow civilisation and reconstitute society on the basis of arrested development, envy, malevolence and impossible equality. Churchill said:

This conspiracy had existed since the days of Spartacus-Weishaupt, and continued through the work of Karl Marx, Trotsky (in Russia), Béla Kun (in Hungary), Rosa Luxemburg (in Germany) and Emma Goldman (in the United States).[10]

Conventional claims that the Marxist-communist doctrine was not correctly ‘interpreted’ by communist dictators in the 20th century are unjustified. The writings of Marx and Engels make it clear that they always proposed violent revolution, the terrorist destruction of societies, and dictatorship as solutions.

After the failure of the 1848 revolution in Germany, Karl Marx wrote that,

… there is only one way in which the murderous death agonies of the old society and the bloody birth throes of the new society can be shortened, simplified and concentrated, and that way is revolutionary terror.[11]

In 1849 Marx wrote: We are merciless and do not demand any clemency. When it is our turn, we will not hide our terrorism.[12]

Together with Engels he spread the idea of revolutionary terrorism as a way to end the traditional society.[13] This is also evident from the Communist Manifesto, which ends with a statement:

The Communists … openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions. Let the ruling classes tremble at a communist revolution…

Moreover, from his early years, Marx in a fanatic fashion fixed his gaze on an end goal – destruction of the traditional human society and its nucleus elements (nation, family, private ownership). British historian Paul Johnson concludes that,

Marx’s concept of a Doomsday … was always in Marx’s mind, and as a political economist he worked backwards from it, seeking the evidence that made it inevitable, rather than forward to it, from objectively examined data.[14]

Professor Richard Pipes has stated that Marxism was dogma masquerading as science. Pretension to “scientific method” was a mask designed to increase appeal, according to the fashion of the times. Bertrand Russell called bolshevism, an offspring of Marxism, which was helped to take power in Russia, a “religion” and spoke of its habit of militant certainty about objectively doubtful matters.[15]

Russia before World War I

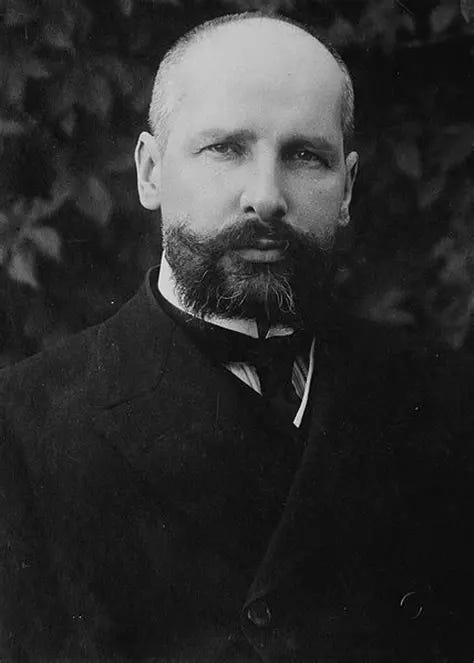

To better understand the motives behind the 1917 revolutions, it is important to examine the situation in Russia at the time. Before the First World War, Russia was in the process of transforming itself from an agricultural to an industrial nation. In July 1906, the Tsar appointed Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin (1862–1911) as Prime Minister. A former successful governor of Saratov and then Minister of the Interior, Stolypin proved to be an outstanding statesman of late Imperial Russia.[16]

Pjotr Arkadievich Stolypin

In 1906-1907, Stolypin initiated major long-term agrarian reforms in Russia that granted the right of private land ownership to the peasantry. He managed to lay the basis for a class of more prosperous, independent peasants – the percentage of those who had ownership over their own land rose from 20 percent in 1905 to that of 50 percent in 1915.

Russia’s agricultural production increased from 45.9 million tonnes in 1906 to 61.7 million tonnes in 1913[17], thus showing the economic benefits of Stolypin’s reforms. Agricultural disturbances also decreased significantly. Russia deserved the name “the world’s granary”.

In 1913, out of the world’s production, Russia produced 67% of rye, 31% of wheat, 32% of oats and 42% of barley. Between 1909 and 1913 Russian production of these four main cereals was 28% greater than the combined production of Argentina, Canada and the United States. The exports of cereals exceeded the corresponding exports of Argentina by 177%, of Canada by 211% and of the USA by 366%.[18]

Moreover, Stolypin’s decisive actions significantly reduced the rampant revolutionary violence perpetrated by socialist and communist terrorists in Russia following the failed 1905 revolution. This violence resulted in thousands of casualties, with 23,000 acts of revolutionary violence killing or wounding nearly 17,000 people between 1901 and 1917, predominantly in the aftermath of the 1905 revolution. Similarly, the number of political assassination attempts fell in 1909 and 1910.[19]

But Stolypin himself had to pay with his life. He is reputed to have said:

I have got the revolution by the throat and I shall strangle it to death … if I live.

“If I live” was no idle statement. There had been already ten attempts on his life.[20] The eleventh attempt succeeded. On September 14, 1911, revolutionary terrorist Mordechai Gershkovich Bogrov (alias Dmitri Bogrov) mortally wounded Stolypin in the Opera House in Kiev at a gala performance and in the presence of the Czar.

It was mainly Pjotr Stolypin’s reforms and the economic prosperity that accompanied them that restored order to Russia. The economy was booming, the village was mainly calm. By 1913, iron production had grown by over 50 per cent compared to 1900, while coal production had more than doubled. The nation’s exports and imports had also doubled.[21] Russia’s industrial production reached an impressive 34 million tonnes of coal and almost 5 million tonnes of steel in 1916.[22]

By 1914, Russia’s industrial production, measured by the output of coal, iron and steel, ranked fourth in the world behind only Germany, Britain and the United States, overtaking even France, Russia’s key economic partner.[23]

In the six years before the First World War, the Russian economy grew at an average annual rate of 8.8 per cent.

Historians Mikhail Heller and Aleksandr M. Nekrich have highlighted that the decade preceding the war had been one of rapid economic growth.[24] Historian Sean Mcmeekin has concluded that even participation in World War I did not bring about any backslide of Russian economy by 1917 – the evidence points instead to a stupendous (if inflationary) wartime boom.[25]

Prof Richard Pipes have pointed put that a French economist forecasted in 1912 that if Russia maintained until the middle of the 20th century the pace of economic growth she had shown since 1900, she would come to dominate Europe politically, economically, and financially.[26]

Before World War I, other European powers were beginning to develop respect for Russia, while also showing increasing concern. Those forces who had planned to overthrow the Czarist regime for good were especially concerned, having made their first major attempt to instigate the 1905 Revolution in Russia.

Money trail from the Western capitalists

Certain powerful financiers were one axis of those forces, which made concerted efforts to bring down the Czarist regime in Russia. They were the representatives of American and European banking and industrial dynasties, the real capitalists of the Western world. As Dr. Antony Sutton has stated:

There has been a continuing, albeit concealed, alliance between international political capitalists and international revolutionary socialists — to their mutual benefit.[27]

Karl Marx and the Wall Street, cartoon by Robert Minor (1911)

Historian Richard B. Spence has emphasized that the Russian Revolution, like every revolution, was by nature conspiratorial[28]:

It is not possible to organize the overthrow of a regime without conspiracy. Business is no different – a trust is a conspiracy, and so are stock raids and corporate takeovers. Conspiracy is not the exception in human behavior, it is the norm.

Jacob Schiff (1847-1920) played a key role in providing and coordinating financial backing to the communist revolutionaries in Russia. He was a Wall Street banker, arms dealer[29] and chairman of the Kuhn, Loeb & Co, which had strong affiliations with the Rothschild’s family.

Schiff played a key role in providing and coordinating financial backing to the communist revolutionaries in Russia. A number of references of his activities and views against the Russian Czarist regime are contained in a book about him by Cyrus Ader “Jacob Schiff, His Life and Letters” (London, 1929). Schiff called Czarist Russia an enemy of humanity and opposed the Romanovs by all means during several phases, already in the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century.[30]

Schiff spent millions to overthrow the Czar (in February 1917) and more millions to overthrow Kerensky’s Government (in October 1917).[31] Journalist and war correspondent George Kennan revealed in March 1917 that Jacob Schiff had been financing Russian revolutionaries through an organisation, the Society of the Friends of Russian Freedom.[32] According to information based on French Intelligence Service, twelve million dollars were reported to have been donated by Schiff to the Russian revolutionaries in the years preceding the war. Schiff openly boasted in spring 1917 that it was thanks to his financial support that the Czarist regime was overthrown in Russia.[33]

On March 23, 1917, a mass meeting of left-radicals was held at Carnegie Hall, New York, to celebrate the abdication of Czar Nicholas II. Jacob Schiff’s telegram was read to this audience, where he described the successful Russian revolution as:

… what we had hoped and striven for these long years.[34]

Jacob Schiff’s great contribution to the communist revolutionaries in Russia was confirmed by Schiff’s grandson John Schiff in 1949, when he estimated that his grandfather sank about 20 million dollars for the final triumph of bolshevism in Russia. Other New York banking firms also contributed.[35]

Schiff’s motives were twofold:

- firstly, to overthrow the Tsar and the Romanov dynasty by any means necessary, and

- secondly, to recoup his “investments”.

He certainly earned his money back: according to the late Russian Imperial Ambassador to the United States, Bakhmetiev, the Bolsheviks transferred 600 million rubles in gold to Jacob Schiff’s company, Kuhn, Loeb & Co., between 1918 and 1922.[36]

There were certainly more financial supporters of the Russian Revolution. The revolutionary communists were subsidised by the likes of the Warburg dynasty, the Rhine-Westphalian Syndicate and Olof Aschberg of Nya Banken in Stockholm.[37]

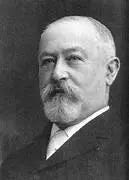

Max Warburg (1867-1946 ), one of the wealthiest bankers in Germany, and industrialist Hugo Stinnes contributed to pro-German and anti-government activities in Russia. On 12 August 1916, Hugo Stinnes agreed to provide 2 million rubles for pro-German peace propaganda. Max Warburg considered the project to be both plausible and profitable.[38]

Max Warburg

One of Max’s brothers, Felix Warburg, was married to Jacob Schiff’s daughter, Frieda Schiff. Another of Max’s brothers, Paul Warburg, married Solomon Loeb’s (Kuhn, Loeb & Co.) daughter Nina Loeb. Both Paul and Felix Warburg became partners in Kuhn, Loeb & Co.[39]

Obadja Asch (alias Olof Aschberg, 1877-1960), a socialist[40] from Sweden who was also known as the ‘Bolshevik banker’, financed the Bolsheviks himself and played a key role in providing financial services. Nya Banken and Aschberg were funnelling funds from the German government to Russian revolutionaries. They also provided a channel through which hundreds of tons of Tsarist gold could be transferred to the West, looted by the communists after the coup d’état in October 1917.

Obadja Asch, alias Olof Aschberg

By 1914, Russia had accumulated Europe’s largest strategic gold reserves, worth nearly 1.7 billion rubles ($850 million), or about 1,200 metric tons. The looting of Russia’s wealth by the Bolshevik gang has been described in detail by historian Sean McMeekin, who has called it the greatest heist in history.[41] The Russian gold reserve was sent abroad, overwhelmingly to Wall Street.[42]

Dr Antony Sutton provided evidence that a working relationship was established between Bolshevik banker Olof Aschberg and the Guaranty Trust Company, controlled by J.P. Morgan, before, during and after the Russian Revolution. During the Czarist era, Aschberg acted as a Morgan agent in Russia, negotiating Russian loans in the United States.

In 1917, he served as a financial intermediary for the revolutionaries, and following the revolution, he became the head of Ruskombank — the first Soviet international bank. Meanwhile, Max May, a vice president of the Guaranty Trust, became the director and chief of the Ruskombank foreign department. There is also evidence of transfers of funds from Wall Street bankers to international revolutionary activities. For example, William Boyce Thompson — a director of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, a major shareholder in Rockefeller’s Chase Bank, and a financial associate of the Guggenheims and Morgans — donated at least $1 million to the Red Revolution for propaganda purposes.[43] Interestingly, the Rockefeller-controlled National City Bank branch in Petrograd was exempted from the Bolshevik nationalisation decree — the only foreign or domestic Russian bank to be granted such an exemption.[44]

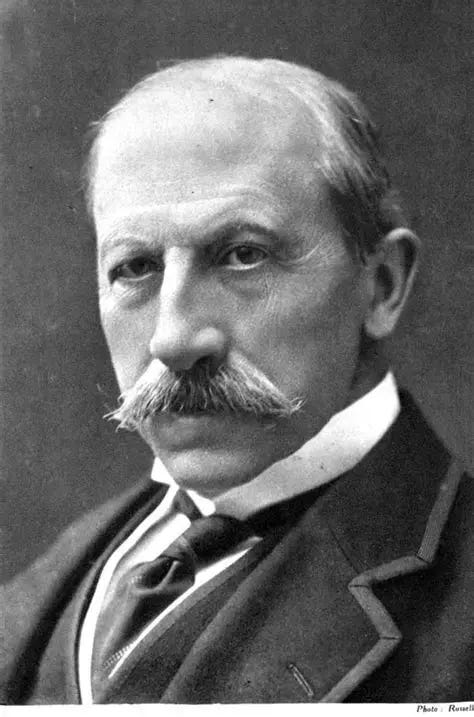

Another financier, Alfred Milner (1854–1925), was a director of the London Joint Stock Bank. From 1916 to 1918, he was also an influential member of the British War Cabinet, alongside three others. He was considered a powerful figure behind the scenes for Prime Minister Lloyd George. Milner was an admirer of Marxist communism. Marx’s great book Das Kapital is a monument to reasoning and a storehouse of facts.[45]

His contribution to the Bolshevik revolutionaries was estimated to exceed 21 million rubles. This money was used to pay the initiators of the revolt in Petrograd. It is alleged that Milner and Lloyd George made the joint decision to support the revolts in Russia in September 1916.[46] Milner also led the British delegation on the mission to Petrograd in January 1917, just three weeks before the February Revolution began. During this mission, it has been suggested that Milner demanded that the Czar dismiss his government; otherwise, there would be a revolution and the Czar would lose his life. The Czar refused.[47]

According to a memorandum from the French military delegation, during the mission, Milner instructed the British ambassador, George Buchanan, to support the revolutionaries in the event of unrest, despite this violating the Entente alliance.[48] An Irish member of the House of Commons, Laurence Ginnell, also stated during a parliamentary debate on 22 March 1917 that Lord Milner had been sent to Petrograd in January 1917 to:

…incite rebellion and foment revolution, dethroning our Imperial Russian ally, the Czar.[49]

Unsurprisingly, neither the conventional history books (e.g. A Concise History of the Russian Revolution by Richard Pipes, The Russian Revolution by Sheila Fitzpatrick, etc.) nor The Black Book of Communism (English edition published by Harvard University Press in 1999) mention the essential role of the financiers of the revolutions, let alone significant financial supporters such as Jacob Schiff, the Warburg dynasty, J. P. Morgan and Alfred Milner.

Without the financial backing of Jacob Schiff alone, for example, it is highly likely that the communists would not have achieved their coup d’état in Russia in 1917. According to modest calculations[50], 20 million USD in 1917 is equivalent to at least 300 million USD nowadays.

German support to the bolsheviks

Besides financial backing from Wall Street, the bolsheviks received substantial support from the German government. Based primarily on archive records, Elizabeth Heresch has conducted extensive research into this collaboration and documented it in her book dating from 2000 – Geheimakte Parvus: Die gekaufte Revolution Biographie. Researcher Z.A.B. Zeman has recorded many important documents in his book Germany and The Revolution in Russia in 1915-1918: Documents from the Archives of the German Foreign Ministry (1958) to show the role of German government in supporting communist revolutionaries in Russia.

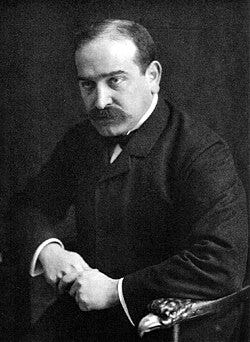

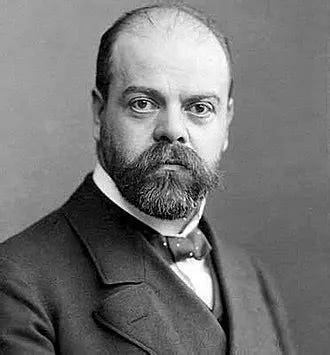

Izrail Lazarevich Helphand (alias Alexander Parvus, 1867-1924) was one of the key persons and a contact between the German government and bolshevik leaders Vladimir Uljanov (alias Lenin) and Leiba Bronstein (alias Lev Trotski). From the spring of 1915 till November 1917, he played the most important part in Germany’s relations with revolutionary movement in Russia.[51]

Izrail Lazarevich Helphand

Parvus had already made up his mind by the time he was eighteen: he wanted to destroy the Czarist state and become rich. He became a Marxist communist, influenced by revolutionaries such as Karl Kautsky, Leon Deutsch, Vera Sassulits and Rosa Luxemburg. He was one of the organisers of the failed 1905 revolution in Russia. From 1910, he was active in Turkey, where he gained organisational and managerial experience and wealth through arms smuggling and other schemes.

His secret collaboration with the German government officially began on March 7, 1915, when he presented a 20-page programme to Gottlieb von Jagow, the State Secretary of the German Foreign Office. The programme set out plans for organising systematic revolutionary activity in Russia in order to overthrow the Czar, establish a communist ‘proletariat’ regime, and end Russia’s participation in the war. On the same day, Jagow requested the initial 2 million marks from the Federal Ministry of Finance to support revolutionary propaganda in Russia, and this sum was soon transferred to various accounts held by Parvus in Copenhagen, Zurich and Bucharest.

Parvus used the services of Olof Aschberg and Stockholm’s Nya Banken to deliver money to Russia for revolutionary operations. He received an additional 4 million marks in spring and 5 million in July, and requested a further 20 million Russian rubles in autumn 1915.[52] Parvus introduced his revolutionary plan, in which Lenin was to play a leading role, to Lenin no earlier than May 1915.[53]

He organised preparations for various revolutionary activities and received support from the German government throughout 1916 and 1917. For example, 5 million marks were delivered to the Bolsheviks through him in March 1917.[54]

In the beginning of 1917, under Parvus’s influence, the German ambassador wired Berlin:

We must unconditionally seek to create in Russia the greatest possible chaos … We should do all we can … to exacerbate the differences between the moderate and extremist parties, because we have the greatest interest in the latter gaining the upper hand, since the Revolution will then become unavoidable and assume forms that must shatter the stability of the Russian state.[55]

Later that year, on December 3, 1917, Richard von Kühlmann, Germany’s Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs reported to the Kaiser Wilhelm II the following:

… It was not until the Bolsheviks had received from us a steady flow of funds through various channels and under varying labels that they were in a position to be able to build up their main organ Pravda, to conduct energetic propaganda and appreciably to extend the originally narrow base of their party…[56]

In July 1917, Germany’s ongoing support for the revolutionary communists was exposed in Russia. On 5 July, the small Petrograd newspaper The Living Word (Živoe Slovo) published damning evidence under the heading ‘Lenin, Ganetski[57] & Co – SPIES’, showing how the Bolsheviks had received money from Germany for their activities in Russia. Following this, others began to publish highly revealing information on the Bolsheviks as German agents. The chief prosecutor was obliged to initiate criminal proceedings against Lenin, Leiba Rosenfeld (also known as Leon Kamenev), Hirsch Apfelbaum (also known as Grigori Zinoviev or Gerson Radomyslsky) and Parvus, among others. Some of them were arrested but released by Prime Minister Kerensky in August 1917. Lenin and Zinoviev escaped to Finland, while Parvus escaped to Switzerland.

Initially Lenin denied the accusations of being a German agent, but later he admitted the fact. On October 20th, 1918, at a meeting in Moscow of the Central Executive Committee, the Red dictator made the following statement:

I am frequently accused of having won our revolution with the aid of German money. I have never denied the fact, nor do I do so now. I will add though, that with Russian money we shall stage a similar revolution in Germany.[58]

Historian Sean Mcmeekin has concluded that it is undeniable that Lenin received German logistical and financial support in 1917, and that his actions, from antiwar agitation in the Russian armies to his request for an unconditional cease-fire, served the interests of Russia’s wartime enemy in Berlin.[59]

Links through Freemasonry

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, special archives in Russia that had been closed to researchers during the communist era were opened. These archives contained secret documents revealing a great deal about Masonic activities in Russia during the 20th century. Notably, many of the key figures involved in the 1917 Revolutions were Freemasons, and a significant proportion of these were highly active within the organisation. This secret organisation played an important role in several historic events, and it is likely that they played a significant role in establishing a communist dictatorship in Russia.

For instance already in 1906 the influential French masonic lodge Grand Orient had promised widest possible assistance to the anti-government plans of the Russian revolutionary elements and had promised to support the Russian revolutionaries “in one way or another”.[60] The masonic journal Cosmos (nr 29) wrote in 1906 the following:

The spirit of our time demands that we take over the leadership of socialism, and some lodges have found the right ways and means to achieve this goal.[61]

According to the minutes of the Grand Lodge of Germany dating 1917, the freemasons concluded:

In fact, anarchist and revolutionary Lenin represents consistently the political ideals of international freemasonry.[62]

All of the members of the Provisional Government, which was led by Prince Georgi Lvov and was formed after the forced abdication of Czar Nicholas II on March 2, 1917, were freemasons.[63] Special archive documents reveal that also many high-ranking communists were members of various masonic lodges, e.g.:

Vladimir Uljanov (alias Lenin), Leiba Bronstein (alias Leon Trotsky), Hirsch Apfelbaum (alias Grigori Zinoviev, alias Gerson Radomyslsky), Leiba Rosenfeld (alias Leon Kamenev), Tobias Sobelsohn (alias Karl Radek), Meyer Wallakh (alias Maksim Litvinov), Yankel-Aaron Solomon (alias Yakov Sverdlov), Julius Zederbaum (alias L. Martov or Julius Martov) etc.

This has been investigated by researchers Nikolai Svitkov,[64] Juri K. Begunov[65], Dr. Oleg Platonov[66], Viktor Ostretsov and others, based on archive documents that were revealed after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The notable key figures of the 1917 revolutions were:

Jacob Schiff

Member of the Jewish masonic order B’nai B’rith[67], which was founded by twelve men on Oct 13, 1843, in New York City. Most of the founders were freemasons and oddfellows.[68]

Historian Viktor Ostretsov has claimed that the main bolsheviks – Uljanov-Lenin, Apfelbaum-Zinoviev, Solomon-Sverdlov, Sobelsohn-Radek, Rosenfeld-Kamenev and Bronstein-Trotsky belonged also to B’nai B’rith.[69]

Alfred Milner

Head of the Round Table Group (formerly called “Association of Helpers”), which was an outer circle of a secret society, called a “Circle of Initiates”. This was formally established on February 5, 1891 by an associate of Rothschild and a wealthy industrialist Cecil Rhodes and had as members Brett Stead (Lord Esher), Lord Arthur Balfour, Sir Harry Johnston, Lord Rothschild, Lord Albert Grey and Alfred Milner.[70]

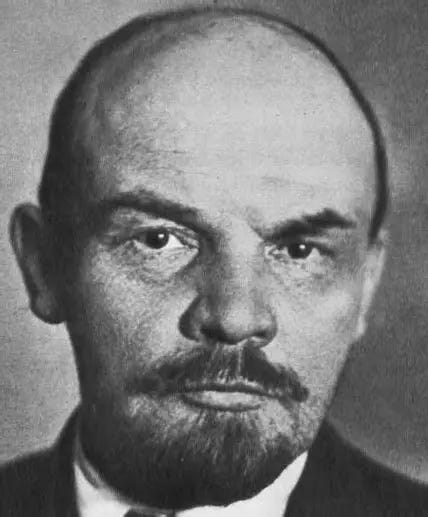

Vladimir Ilich Uljanov (alias Lenin)

Several sources describe his various masonic activities[71], e.g. according to researcher Juri K. Begunov, he was a member of Art et Travail in France, where he attained the 31st degree[72]. According to Nikolai Svitkov, Lenin was initiated into freemasonry as early as 1908.[73] Also, he became a member of a masonic order B’nai B’rith.[74]

Leiba Bronstein (alias Lev Trotsky)

He wrote in his memoirs “My Life” that he studied freemasonry thoroughly for several months, filled an exercise-book with thousand numbered pages with his notes on the subject. Also that:

“…In the 18th century, freemasonry became expressive of a militant policy of enlightenment, as in the case of the Illuminati, who were the forerunners of revolution…”

Bronstein was initiated into freemasonry[75] and was a member of French lodge Art et Travail.[76] He reached at least the 32nd degree in it, as he belonged to the Shriner Lodge, which comprised only of 32nd degree freemasons.[77] In January 1917 Bronstein also became the member of a masonic order B’nai B’rith.[78]

Aaron Kürbis (alias Alexander Kerensky)

Became a freemason in 1912. He was a member of the lodge Grand Orient in Paris, France[79] and a member of the Supreme Council of Russian Freemasonry.[80]

Kerensky acted as the General Secretary of the Supreme Council of the Grand Orient (Veliky Vostok) in Russia in 1916.[81] According to prof Johan von Leers, Kerensky was a member of the Shriner Lodge, which comprised only of 32nd degree freemasons.[82]

Izrail Lazarevich Helphand (alias Aleksander Parvus)

A freemason according to several sources.[83]

(Continues as The 1917 February and October coups, Part 2)

Notes

[1] Arsene de Goulevitch Czarism and the Revolution (1962), p 226

[2] Jüdische Lexicon (Berlin, 1928), pp 1577-1578

[3] Sydney Hook Karl Marx and Moses Hess in New International, Vol 1 Nr 5 (1934)

[4] Moses Hess The Holy History of Mankind and Other Writings, p 87

[5] Juri Lina Under the Sign of the Scorpion (2014), p 100

[6] Ibid, pp 108-109

[7] Vladimir Istarkhov The Battle of the Russian Gods (2000), p 154

[8] Adam Weishaupt (1748-1830), the founder of the secret society Illuminati, which was established on the 1st of May, 1776 in Ingolstadt, Bavaria

[9] Nesta Webster World Revolution (1921), p 169

[10] Rt. Hon. Winston S. Churchill Zionism versus Bolshevism, published in Illustrated Sunday Herald, February 8, 1920, page 5

[11] “Neue Rheinische Zeitung” (nr 136), November 6, 1848

[12] Arnold Kunzli Karl Marx: Eine Psychographie (1966)

[13] Marx and Engels Works, volume 5, p 494

[14] Paul Johnson Intellectuals: From Marx and Tolstoy to Sartre and Chomsky (1990), 162/1069 (epub)

[15] Richard Pipes Communism. A History (2001), 22/300 (epub)

[16] Richard Pipes A Concise History of the Russian Revolution (1996), p 47

[17] D. Murphy Russia in Revolution 1881-1924: From Autocracy to Dictatorship (2008), p 39

[18] From The Bulletin of the International Institute of Agriculture in Rome, November 1914

[19] Anna Geifman Death Orders: The Vanguard of Modern Terrorism in Revolutionary Russia (2010), p 15

[20] Arsene de Goulevitch Czarism and the Revolution (1962), p 228

[21] Richard Pipes A Concise History of the Russian Revolution (1996), p 54

[22] Elisabeth Heresch Blood on the Snow (1990), p ix-x

[23] Sean Mcmeekin History’s Greatest Heist: The Looting of Russia by the Bolsheviks (2009), pp xvi-xvii

[24] Mikhail Heller, Aleksandr M. Nekrich Utopia in Power: The History of the Soviet Union from 1917 to the Present (1986), p 15

[25] Sean Mcmeekin The Russian Revolution (2017), Introduction, 22/1026 (epub)

[26] Richard Pipes A Concise History of the Russian Revolution (1996), p 54

[27] Antony Sutton Wall Street and The Bolshevik Revolution (1981), p 8

[28] Richard B. Spence Wall Street and the Russian Revolution: 1905-1925 (2017), introduction

[29] Elisabeth Heresch Geheimakte Parvus: Die gekaufte Revolution Biographie (2000), Russian ed., 8/665 (epub)

[30] Ibid, 53/665; 206/665 (epub)

[31] Gary Allen, Larry Abraham None Dare Call It Conspiracy (1976), p 43

[32] George Kennan Pacifists Pester Till Mayor Calls Them Traitors in The New York Times, March 24, 1917

[33] Arsene de Goulevitch Czarism and the Revolution (1962), p 225

[34] G. Edward Griffin The Creature from Jekyll Island (1998), p 264-265; The New York Times, March 24, 1917, p 2

[35] In the edition of The New York Journal-American, February 3, 1949

[36] Arsene de Goulevitch Czarism and the Revolution (1962), p 225

[37] General Alexander Nechvolodov The Emperor Nicholas II and the Jews (Paris, 1924), pp. 97-104

[38] Z.A.B. Zeman Germany and the Revolution in Russia, 1915-1918: Documents from the Archives of the German Foreign Ministry (1958), p 92

[39] Gary Allen, Larry Abraham None Dare Call It Conspiracy (1976), p 26 (pdf)

[40] Richard B. Spence Wall Street and the Russian Revolution: 1905-1925 (2017), chapter 6, (296/706 epub)

[41] Sean Mcmeekin History’s Greatest Heist: The Looting of Russia by the Bolsheviks (2009)

[42] Richard B. Spence Wall Street and the Russian Revolution: 1905-1925 (2017), chapter 10, (562/706 epub)

[43] Antony Sutton Wall Street and The Bolshevik Revolution (1981), p 133

[44] Ibid, p 60

[45] Antony Sutton Wall Street and The Bolshevik Revolution (1981), p 64

[46] Arsene de Goulevitch Czarism and the Revolution (1962), p 230; Elizabeth Heresch Geheimakte Parvus: Die gekaufte Revolution Biographie (2000), Russian ed., 316/665 (epub)

[47] Juri Lina Under the Sign of the Scorpion (2014), p 259

[48] Elizabeth Heresch Geheimakte Parvus: Die gekaufte Revolution Biographie (2000), Russian ed., 408/665 (epub)

[49] Parliamentary Debates. House of Commons March 22, 1917, Vol 91, Col 2093

[50] Historian Sean Mcmeekin considers figure of 100 to 1 for converting dollar figures of 1917–1922 to current suggested values – in History’s Greatest Heist: The Looting of Russia by the Bolsheviks (2009): A Note on the Relative Value of Money Then and Now

[51] Z.A.B. Zeman Germany and the Revolution in Russia, 1915-1918: Documents from the Archives of the German Foreign Ministry (1958), p viii

[52] Elizabeth Heresch Geheimakte Parvus: Die gekaufte Revolution Biographie (2000), Russian ed., 352/665 (epub)

[53] Ibid, 228/665 (epub)

[54] Ibid, 458/665 (epub)

[55] Richard Pipes A Concise History of the Russian Revolution (1996), p 116

[56] Z.A.B. Zeman Germany and the Revolution in Russia, 1915-1918: Documents from the Archives of the German Foreign Ministry (1958), p 94

[57] Jakub Fürstenberg (alias Yakov Ganetsky) was one of the closest associates to Lenin, served as a contact person between Lenin and Parvus and provided several other services to Lenin

[58] A.I. Spiridovitch “History of Bolshevism in Russia”, Russian ed., p 226

[59] Sean Mcmeekin Was Lenin a German Agent? in *The New York Times *(June 19, 2017)

[60] Oleg Platonov The Secret History of Freemasonry (2000), Russian ed., p 130 (pdf)

[61] Viktor Ostretsov Freemasonry, Culture and Russian History (1999), Russian ed., 1478/1863 (epub)

[62] Moscow Special Archive, fund 1412-1-9064 and 815; Viktor Ostretsov Freemasonry, Culture and Russian History (1999), Russian ed., p 585 or 1478/1863 (epub)

[63] Sean Mcmeekin The Russian Revolution (2017), chapter 1, Twilight of the Romanovs; also Oleg Platonov Criminal history of freemasonry 1731-2004 (1995), Russian ed., chapter 19

[64] Nikolai Svitkov Freemasonry amongst Russian emigrates (1966), Russian ed.

[65] Juri K. Begunov Tajnye Sily w Istorii Rossij (Secret Forces in the History of Russia) (1996)

[66] Oleg Platonov The Secret History of Freemasonry (2000), Russian ed.

[67] Viktor Ostretsov Freemasonry, Culture and Russian History (1999), 1562/1863 (epub)

[68] Schmidt, Greenwood Encyclopaedia of American Institutional Fraternal Organizations (1980), p 52

[69] Viktor Ostretsov Freemasonry, Culture and Russian History (1999), pp 582-583, 1471/1863 (epub)

[70] Prof Carroll Quigley Tragedy and Hope. A History of the World in Our Time (1966), p 131

[71] Richard B. Spence What Role did Freemasons and Bolsheviks play in the Russian Revolution? (July 9, 2020):

[72] Oleg Platonov The Secret History of Freemasonry (2000), Russian ed., p 285 (rtf)

[73] Nikolai Svitkov Freemasonry amongst Russian emigrates (1966), Russian ed.

[74] Viktor Ostretsov Freemasonry, Culture and Russian History (1999), pp 582-583

[75] Richard B. Spence What Role did Freemasons and Bolsheviks play in the Russian Revolution? (July 9, 2020)

[76] L.Hass Freemasonry in Central and Eastern Europe (1982)

[77] Prof Johan von Leers The Power behind the President (1941), p 148

[78] Juri K. Begunov Tajnye Sily w Istorii Rossij (“Secret Forces in the History of Russia”) (1996), pp 138-139

[79] Oleg Platonov The Secret History of Freemasonry (2000), Russian ed., chapter 8, p 141 (rtf)

[80] Oleg Platonov Criminal history of freemasonry 1731-2004 (1995), Russian ed., p 43 (pdf)

[81] Viktor Brachev The Victorious February 1917: The Masonic Trail (2007), Russian ed., p 134

[82] Prof Johan von Leers The Power behind the President (1941), p 148

[83] Nikolai Svitkov Freemasonry amongst Russian emigrates (1966), Russian ed.