Saturn, Sabbath, & The Cube: Part II – A dark god: a dark legacy…

Mon 1:34 pm +00:00, 28 Oct 2024

Source: https://dfreality.substack.com/p/saturn-sabbath-and-the-cube-part-ii

Throughout mankind’s history, the worship of Saturn — and all his many manifestations — has evinced itself as one of the most grotesque expressions of idolatry. Saturn, known as Cronos/Kronus in Greek mythology, became a symbol of the cyclical destruction and consumption of life. Many disparate ancient civilizations engaged in rituals to appease this dark deity, almost universally through the offering of human lives — most notably, the lives of children — as sacrifices.

Holy Writ stands in stark opposition to this practice, repeatedly condemning it in the strongest terms. Yet, time and time again, we find the tribes of Israel succumbing to the same temptations that ensnared their pagan neighbors. The worship of Ba’al, Moloch, and other deities tied to Saturn’s image wormed their way into their culture: in the wilderness and the Promised Land alike, Israel struggled to remain of the world, but not in it.

The first part of this essay established the historical roots of Saturnian worship and its voluminous connections to human sacrifice and sexual debauchery, tracing this influence from the Amorite religion into the broader cultural practices of the Mediterranean peoples. The Saturnian cultus is also tied deeply to magickal cannibalism — a practice whereby adherents believe that through consuming vital essences, they could transcend the boundaries of time and space. We also explored the compelling Scriptural evidence for the Saturnian corruption of the tribes of Israel; how that bore itself out in the syncretistic, antinomian religion of the Pharisees; and the repeated denunciations of these practices by Jesus Christ and His Apostles.

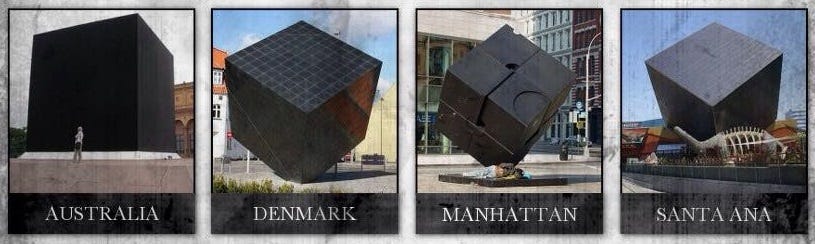

The endurance of Saturn’s influence on astrological, religious, & esoteric lore — particularly the enigmatic “Black Cube” — and the continued veneration of this Saturnian relic is impossible to ignore (emphasis mine):

…Saturn’s physical presence in this world — his idol, if you will — is said to be a black stone, cube, or obelisk. … The Kaaba [at Mecca] itself, which was originally an icon of the Time deity, is another prominent example of the Black Cube. … Further, the symbol or emblem of the Black Cube appears in many contemporary art and media projects, often as a symbol of alien menace or alterity. Examples include Clive Barker’s Hellraiser cubes, and the Leviathan deity itself. Even a Google search for ‘Black Cube’ shows an extensive list of corporations that use the Black Cube as a symbol, or actual Black Cubes that are installed around the world.

— Arthur Moros, The Cult of the Black Cube

The Saturnian gnostic and occultist Arthur Moros reveals that the Cube is not just a prolific esoteric symbol — it is the embodiment of the Saturnian entity. The controversial “private” Israeli intelligence firm, Black Cube, bears this name as well. Also of note is the fact that the surface of Saturn itself bears a hexagonal pattern, one which amateur astronomers have captured from Earth.

Thus, the Cube represents the ultimate prison — both a vessel of mortality and a gateway to the deeper, forbidden power of this death god.

— Black cube “art” installations across the world.

— The Kaaba in Mecca, Saudi Arabia.

— “Tefillin (תְּפִלִּין) are a pair of black leather boxes containing Hebrew parchment scrolls.” Source: Chabad.org.

Given this historical context, one finds a fascinating and unsettling connection between Saturn and the Jewish Sabbath, or Shabbat.

While these ancient rites may seem alien to the modern mind, the troubling reality of Saturnian worship continues to surface throughout ethnic Israel’s history; finding its expression not just in overt paganism but also in syncretistic elements that persist even after the first and second Babylonian exile. Despite clear denunciations in both the Old and New Testaments, the subtle infiltration of the Saturnian cultus is undeniable — particularly in areas where mysticism, numerology, and certain esoteric traditions such as astrology have surfaced. As the Jewish scholar Ariel Toaff puts it, Judaism is “a world drenched with magickal rites and exorcism, within whose mental horizons popular medicine and alchemy, occultism and necromancy were often mixed, finding a position of their own, influencing and reversing the meaning of ordinary religious standards.” (Toaff, 2007)

The Babylonian Talmud refers to Saturn as Shabbetai, the star of Shabbat, a nod to the planet’s astrological influence over the seventh day within Rabbinic Judaism. Medieval Jewish astrologers, such as Abraham Ibn Ezra, confronted this uncomfortable association within the Talmud, striving to explain how Saturn’s connection to Saturday could be reinterpreted within his religious framework (emphasis mine):

The provenance of Ibn Ezra’s astrology was of course Jewish in so far as he cited many Talmudic passages that discussed the influence of the stars and planets. But it contained much more from non-Jewish works of astrology. His work was “an accumulation of sources and doctrines that go back to the very beginnings of the astrological literature.” [12] This includes ancient Egyptian and Babylonian sources, as well as later Hellenistic works by Ptolemy.

For Ibn Ezra, this link did not signify corruption but rather served as an opportunity for his people to rise above worldly concerns, to devote the Sabbath to their misguided worship of Yahweh — albeit, still in fear of Saturn. However, the Tanakh (which Rabbinic Judaism allegedly claims to follow) explicitly condemns this pagan astrological fatalism (Jeremiah 10:2).

The alleged ties to Saturn within Talmudic Judaism is nothing less than post-hoc rationalizations by the Rabbis for their Saturnian idolatry.

“9 Will ye steal, murder, and commit adultery, and swear falsely, and burn incense unto Baal, and walk after other gods whom ye know not;

10 And come and stand before me in this house, which is called by my name, and say, We are delivered to do all these ABOMINATIONS?

11 Is this house, which is called by my name, become a den of robbers in your eyes? Behold, even I have seen it, saith the Lord.”

— The Book of Jeremiah 7:9-11 KJV

Given the close ties between the Saturnian cultus and ritual sacrifice, it would hardly be proper to overlook the numerous accusations of ritual sacrifice and cannibalism — the infamous “blood libel” — against Jewish communities that have surfaced repeatedly throughout history.

Apion, an Egyptian grammarian that lived from ~30–20 BC – 45–48 AD, was one of the first gentiles to hurl the accusation of human sacrifice against the Alexandrian Jews. His claims — intended to stir up anti-Jewish sentiment against the large Jewish populace of Alexandria — alleged that Jews annually sacrificed a Greek victim in their temple to fulfill their religious obligations. The Jewish historian Josephus responded with a scathing refutation of Apion’s accusations in his apologetic work, Against Apion. Apion’s claims, while baseless in their specific allegations, are nonetheless significant in that it establishes this claim as an enduring one, almost certainly drawn from stories of prior Canaanite practices. As the Jewish Medieval scholar Ariel Toaff notes in his seminal & controversial work on the topic, Passover of Blood, such fears were particularly heightened in Europe during the rise of the Mediterranean Jewish slave trade, which by the “time of Pope Gregory the Great (590-604) Jews had become the chief traders in this class of traffic.” (Jewish Encyclopedia)

Perhaps the most infamous episode that illustrates this dark narrative is the case of Simon of Trent, a three-year-old boy whose tragic death in 1475 has became a focal point in the discussion around the blood libel. After the body of Simonino was found exsanguinated in the cellar of a Jewish home, numerous locals, including the head of the Jewish of community of Trent, were arrested. Torture was used to procure confessions of the heinous crime before sixteen of the conspirators were burnt at the stake.

While many historians handwave such confessions away due to the circumstances of their procurement, to dismiss all confessions extracted via torture as inherently unreliable is a gross oversimplification. In the wake of Abu Ghraib and the excesses of the so-called “War on Terror,” this particular notion seems to largely rest on neurophysical studies that focus merely on the mind’s frailty whilst neglecting to address the substance of the matter: whether the information acquired is factual or not. In medieval jurisprudence, any confessions obtained via torture had to be secured in a separate interrogation without the application of torture. Putting the morality or immorality of such actions aside, truth can indeed be gained under duress. The frailty of the mind does not falsify the factual.

In 1755, Pope Benedict XIV apologized for the Catholic Church’s treatment of European Jewry in his papal bull, Beatus Andreas. While seeking to correct historic injustices wrought by such accusations, this papal decree nevertheless continued to accept Simonino’s ritual murder as a historical fact (emphasis mine):

I therefore admit as true the fact of the sainted Simon, the boy of three years of age killed by Jews in hatred of the faith of Jesus Christ in Trent in the year 1475 […] I accept as true another crime, committed in the village of Rinn, diocese of Bressanone, in 1462, against the sainted Andrea, a boy barbarously killed by the Jews in hatred of the faith of Jesus Christ […] I do not, however, believe, even admitting as true the true facts of Bressanone and Trent, that one can justifiably deduce that this is a maxim, either theoretical or practical, of the Hebrew nation, since two events alone are insufficient to establish a certain and common axiom.

— Beatus Andreas, 1755

Beatus Andreas proclaimed Simon a martyr and called for the veneration of his memory while it simultaneously sought to exonerate the Jewish community as a whole from the charges that had plagued them since the medieval era.

I find myself largely in agreement with Benedict’s opinion that these murders were “exceptional events, not to be generalized, but were nevertheless concrete and real,” (Toaff, 2007) and as such, these admittedly extreme cases can hardly be laid at the feet of all of Jewry. One would certainly not mistake me for a philosemite, but throwing around such cavalier charges only retards the efforts to expose the incontrovertible pagan influences within Rabbinic Judaism. Nonetheless, it is hard to argue that this uniquely depraved form of corruption, however rare it may or may not be, is anything less than a faithful representation of Saturnian devotion.

While modern historians have largely chalked up these claims to the feverish imagination of anti-Semitic inquisitors and Hellenistic propagandists, there is indisputably a tradition of magickal cannibalism within Rabbinic Judaism — a fact which Jewish historians and religious writings have documented at length.

— Bas-relief of the murder of Simon of Trent in the Palazzo Salvadori, Trento, Italy.

In the centuries following Apion, the rise of Kabbalah and other mystical Jewish traditions only added further fuel to the fire of these accusations. With its occultic focus on hidden knowledge and grisly esoteric rituals, Kabbalah openly embraces numerology, magickal incantations, and haemoalchemy:

The texts of the practical Cabbalah, the handbooks of stupendous medications (segullot), compendia of portentous electuaries, recipe books of secret cures, mostly composed in the German-speaking territories, even very recently, stress the haemostatic and astringent powers of young blood, above all, on the circumcision wound. These are ancient prescriptions, handed down for generations, put together, with variants of little importance, by cabbalistic herb alchemists of various origins, and repeatedly reprinted right down to the present day, in testimony to the extraordinary empirical effectiveness of these remedies…

— Ariel Toaff, Passover of Blood

As Professor Toaff notes, such practices had been “handed down for generations,” attesting to the long running and pernicious influence of mystical and magickal praxis within Rabbinic Judaism. Moreover, Toaff’s survey of Rabbinic and Kabbalistic writings reveal that the assertion that Jewish communities throughout the Germanic territories historically consumed potions and medications derived from animal blood “appears to be incontrovertibly confirmed by authoritative and significant Hebraic texts…” (Toaff, 2007). This only further lends credence to the idea that particular strains of Judaism ventured into morally and religiously dubious territory.

Toaff goes even further, unveiling a macabre and, frankly, revolting tradition found amongst numerous Jewish communities (emphasis mine):

One form of magical cannibalism, related to circumcision, may be found in a custom highly widespread among both the Ashkenazi Jewish communities and communities of the Mediterranean region. The women present at the circumcision ceremony but not yet blessed with progeny of the male sex, anxiously awaited the cutting of the foreskin of the child. At this point, throwing inhibition to the winds, as if at a pre-established signal, the women hurled themselves upon that piece of bloody flesh. The luckiest woman is alleged to have snatched it up and gulped it down immediately, before she could be mobbed by the competing females … The struggle for the foreskin among women without male progeny appears in some ways similar to today’s competition among spinsters and nubile young girls for the conquest of the bride’s bouquet after the wedding ceremony.

— Ariel Toaff, Passover of Blood

As a well known and respected Medieval scholar with unique access to Rabbinic documentation, Toaff’s book can not simply be dismissed as the musings of a fringe conspiracist. This ghastly magickal cannibalism is linked intimately to the act of circumcision in Rabbinic literature, raising unsettling questions about the religious and cultural motivations that underpin such acts. Despite the clear Mosaic commands against the ingesting of blood and human flesh, Rabbinic commentaries in the Talmud also state that “there is no prohibition against usefully benefiting from the dead bodies of Gentiles.”

These examples serve as inarguable proof that a deeply rooted spiritual rebellion, typified in the rejection of Christ in the flesh, allowed for the metastasizing of pagan, proto-Gnostic, and Babylonian influences (emphasis mine):

…in continual movement, profound currents of popular magic had, over time, distorted the basic framework of Jewish religious law, changing its forms and meanings. It is in these “mutations” in the Jewish tradition – which are, so to speak, authoritative – that the theological justification of the commemoration [in mockery of the Passion of Christ] is to be sought, which, in addition to its celebration in the liturgical rite, was also intended to revive, in action, vengeance against a hated enemy, continually reincarnated throughout the long history of Israel (the Pharaoh, Amalek, Edom, Haman, Jesus).

— Ariel Toaff, Passover of Blood

Kabbalah is as clear a manifestation of the post-Covenant Jewish community’s spiritual decay as one could ask for. The influence of Babylonian mysticism, now fully absorbed, combined with Platonic and proto-Gnostic elements, created an environment ripe for the kinds of ritual accusations that have been swirling since the time of Apion.

While Christianity emphasizes spiritual renewal through the symbolic washing of the blood of Christ, certain mystical Jewish sects and teachings have clearly used blood for occult and magickal purposes. These practices should be seen not merely as isolated instances of deviance, but symptoms of a broader, corrupted tradition that runs counter to the true Abrahamic faith. Since the Law was fulfilled in Christ, these dangerous mystical traditions should be recognized for what they are: gross perversions of the sacred liturgies of the Old and New Covenant; yet, faithful representations of the Saturnian religion.

“Blessed art thou, Lord, who cancels and allows the prohibitions.”

— Sabbatean Proverb

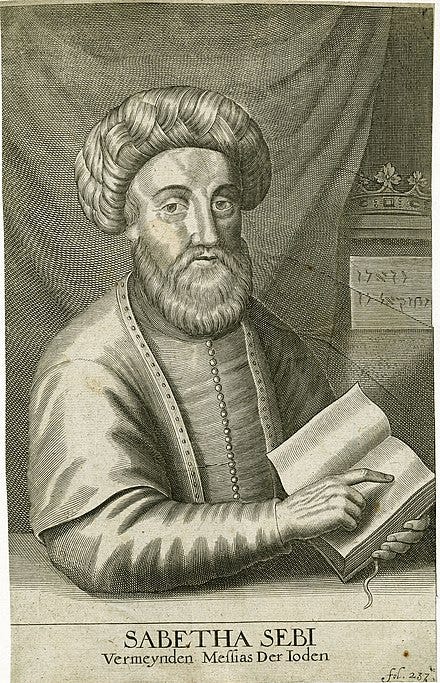

Led by Sabbatai Zevi in the 17th century, the Sabbatean movement offers yet another example of this spiritual descent.

The movement emerged in the mid-17th century, representing a significant deviation from even mainstream Rabbinic thought. It was profoundly influenced by ancient pagan practices — especially those associated with Saturnian worship. This schismatic antinomian cult was led by the charismatic figure of Sabbatai Zevi, a megalomaniac who declared the onset of the messianic era on June 6th, 1666. Zevi’s movement embraced a radical reinterpretation of Jewish law, promoting the idea that the written Torah “was to be actively and deliberately violated.” (Scholem, 1971) It should be no marvel to find such antinomian fervor amongst the more mystical elements of Jewish thought, as this rebellion against Yahweh’s laws forms the foundation of the Rabbinic faith.

At the heart of Sabbatean theology was the belief that this false messiah’s ascension marked the dawn of a new era in which the old laws were not merely reinterpreted, but outright annulled:

The main concept in Sabbatean theology was relying on the concept that after Shabtai Zvi entered the Jewish arena, the messianic era has started. In this new world, everything was turned upside down: the old law was cancelled, all the “do not” laws became “do” laws, even strong prohibitions such as Incest. The Sabbatean used to bless each other with this (twisted) verse: “Blessed art thou, Lord, who cancels and allows the prohibitions.”

— Sacred Orgies: the Extremist Sabbatean Sect of Jacob Frank

The Sabbatean movement drew upon elements of Saturnalia, a Roman harvest festival characterized by revelry, moral license, and the inversion of social norms. Ultimately, the Sabbateans adopted these practices in their twisted attempts to immanentize the eschaton.

Jacob Frank, a later disciple of Sabbatean thought, took these ideas even further, incorporating occultism and unspeakably vile sexual acts into his teachings (emphasis mine):

The story of the Frankist sect started with the founder and leader, Jacob Frank. Born in Podolia in 1726 to a wealthy family from the inner circle of the Sabbatean [movement] … Upon his return to Poland in 1755 he started to develop a severe megalomania, deeply convinced that he was the true successor of Shabtai Zvi.

Frank addressed his followers: “I came not to elevate your spirits, but to humiliate you to the bottom of the abyss, where you can get no lower, and where no man can rise from by his own forces, but only God can pull him with his mighty hand from the depth.” By “abyss” he meant particularly sexual rituals that included sacred orgies with just a touch of incest.

— Sacred Orgies: the Extremist Sabbatean Sect of Jacob Frank

A sect which embraced orgiastic rites, and other vile sexual practices, represents the furthest extreme of antinomianism that has taken root within the Jewish religion. Frank and Zevi are clear examples of how far one can fall when they reject Christ — the true Messiah.

— Sabbatai Zevi (1626 — 1676), Jewish mystic and false messiah.

The intertwining of Sabbateanism with Kabbalah further elucidates this narrative for us.

Kabbalah readily presents an experiential and subjective framework where the relationship between the sacred and the profane can be easily manipulated. The Sabbateans heavily utilized Kabbalistic concepts to lend legitimacy to their ideas: they suggested that the breaking of laws was necessary to reveal deeper spiritual truths, akin to the Kabbalistic notion of the “breaking of vessels”: divine light dispersed into the world through acts of ritual transgression. This merging of Kabbalistic thought with the celebration of moral nihilism created a potent ideological mixture that allowed followers to justify their actions as a means of achieving a higher spiritual state.

Secular scholarship has tried to vociferously downplay the influence of Sabbatean philosophy on modern Judaism — this despite reports that nearly half of European Jewry adhered to some form of the doctrine during Zevi’s heyday. In 1971, noted Jewish scholar Gershom Scholem attempted to answer the question of why Sabbateanism has largely been swept under the rug by Jewish historians (emphasis mine):

Secularist historians, on the other hand, have been at pains to de-emphasize the role of Sabbatianism for a different reason. Not only did most of the families once associated with the Sabbatian movement in Western and Central Europe continue to remain afterward within the Jewish fold, but many of their descendants, particularly in Austria, rose to positions of importance during the 19th century as prominent intellectuals, great financiers, and men of high political connections. …

The “believers” endeavored to marry only among themselves, and a wide network of inter-family relationships was created among the Frankists, even among those who had remained within the Jewish fold. Later Frankism was to a large extent the religion of families who had given their children the appropriate education.

— Gershom Scholem, “The Holiness of Sin,” Commentary Magazine, vol. 51, no. 1 (January 1971)

As Scholem notes, this historical amnesia seems tactical in nature to minimize the significance of Sabbateanism, as the families associated with this radical movement in Western and Central Europe did not simply vanish from the annals of Jewish history.

Moreover, the refusal of these families to sever ties with their Sabbatean past reveals a persistent undercurrent of ideological and cultural continuity. Even as they publicly aligned themselves with mainstream Jewish thought, the legacy of these radical roots almost certainly informed their religious perspectives and actions. This trend can be observed in Austria, where Frankists became influential intellectuals and financiers. It is also inarguable that Sabbatean Frankism directly led to the formation of Orthodox Judaism, in reaction to it, and Reformed Judaism, as an extension of it.

In conclusion, Scholem’s analysis points us to a crucial insight: the remnants of Sabbateanism, particularly through Frankism, have left an indelible mark on the contemporary Jewish mind.

“26 But ye have borne the tabernacle of your Moloch and Chiun your images, the STAR of your god, which ye made to yourselves.”

— The Book of Amos 5:26 KJV

While I do not think Romans 11 is speaking of the future national conversion of ethnic Israel, I legitimately think there is still hope for a remnant of the Jewish people.

It is essential to consider this chapter in the broader context of the Apostle Paul’s argument, which stretches from Romans 9 to 11. Paul clearly distinguishes between two Israels: “They are not all Israel, which are of Israel: Neither, because they are the seed of Abraham, are they all children” (Romans 9:6-7). This defines who the true Israel is — the Israel of faith, those who trust in Christ. So when Paul later says, “And so all Israel shall be saved” (Romans 11:26), it would truly be bizarre if he were referring to a future, collective, national salvation of ethnic Jews since he says mere sentences before they must not persist in their unbelief in order to be grafted into The Vine (i.e. to be saved) (Romans 11:23).

The olive tree metaphor demonstrates this: branches were broken off because of unbelief, and Gentiles were grafted in by faith. This is not about ethnicity but about belief. Paul’s argument throughout this and his other epistles is that the salvation of Israel is based upon their faith, not their genealogy, however pure or impure that may be. The remnant of faithful Judeans, those who embrace Jesus as the true Messiah, are part of this salvation alongside believing Gentiles. So, in this sense, “all Israel”, the full number of the elect in Christ — both Judean and Gentile — will be saved by faith.

The culmination of this exposition is exemplified in the warning offered by Jesus to That Wicked Generation (emphasis mine):

43 When the unclean spirit is gone out of a man, he walketh through dry places, seeking rest, and findeth none.

44 Then he saith, I will return into my house from whence I came out; and when he is come, he findeth it empty, swept, and garnished.

45 Then goeth he, and taketh with himself seven other spirits more wicked than himself, and they enter in and dwell there: and the last state of that man is worse than the first. Even so shall it be also unto this wicked generation.

— The Gospel of Matthew 12:43-45 KJV

Instead of embracing the fullness of the faith revealed through and in Christ, the vestiges of the Saturnian cultus — astrology, haemoalchemy, and ritual magick — reasserted themselves, leaving the Pharisees and their spiritual offspring even more wicked than they had been before the Crucifixion.

To curse Edom is to curse themselves; to rail against Canaan is to rage against their own house.

Whether through the pagan mysticism of Kabbalah, the debauchery of the Sabbateans, or the ritual accusations that have haunted Jewish communities for centuries, these accusations — however much they have or have not been exaggerated — clearly point to far deeper spiritual issues.

— The Cube II, digital art, 2024.

While this is certainly a topic fraught with controversy, the accusations of ritual cannibalism and human sacrifice against the Jews are not without a grain of truth, however small that may be. The historical record, as recorded by Jewish historians and theologians, elucidates the fact that the spiritual vacuum left by their rejection of Christ has led the Israel of the flesh into dangerous and unholy practices.

The examination of the Saturnian cultus and its insidious influence upon the religious practices of ancient Israel — as well as later Rabbinic tradition — reveals a profound self-deception.

The historical analysis presented throughout this series underscores the tragic irony of a people chosen to bear witness to the one true God, yet falling prey to the very practices they were commanded to shun. Judaism, which ostensibly claims allegiance to the Torah — the very Scriptures that resound with denunciations of the devices of Ba’al, Moloch, and planetary deities like Saturn — has, to varying degrees, absorbed practices and beliefs that mirror the very idolatry it professes to condemn. Indeed, this is particularly striking in light of Judaism’s imprecatory invocations against Edom and Canaan, as the mingling of bloodlines throughout Jewish history complicates this alleged dichotomy significantly: recent DNA analysis has confirmed that Jewish genetic admixture has significant overlap with these Semitic groups.

The profound irony of “G-d’s chosen people” potentially being the genetic and spiritual descendants of the very groups they curse cannot be overstated.

“13 Wherefore the Lord said, Forasmuch as this people draw near me with their mouth, and with their lips do honour me, but have removed their heart far from me, and their fear toward me is taught by the precept of MEN:”

— The Book of Isaiah 29:13 KJV