“The Spike in Heart Attacks Has Coincided With the Vaccinations”: An Emergency Department Doctor on What’s Behind the NHS Crisis

Wed 11:50 am +00:00, 12 Oct 2022

Emergency Department: Doctors, Nurses and Surgeons Move Seriously Injured Patient Lying on a Stretcher Through Hospital Corridors. Medical Staff in a Hurry Move Patient into Operating Theater.

There follows a guest post by an NHS Emergency Department doctor on what, from his frontline vantage point, is behind the current hospital blockages and ambulance delays. This article first appeared on the website of the Health Advisory and Recovery Team (HART), a group of experts offering a second opinion on COVID-19 policy. Sign up for updates here.

As Emergency Department doctors, we were always going to be on the frontline. In spring 2020, we were taken to one side and it was suggested we might have to say goodbye to our relatives for the foreseeable future. Few realise the fear generated in hospitals in 2020. As Emergency Department consultants we were put on 24/7 emergency shift rotas and provided with vacant hotel rooms to live away from our families for their protection. Many of our colleagues left us to it and, soon after, patients arrived showing us signs that had been put up on their GP’s door saying “closed due to the pandemic”.

Spring 2020 saw a combination of assessing and treating sick patients who had unusual and characteristic presentations of Covid in an otherwise quiet Emergency Department. The less-sick patients queued in their cars for assessment in the rapidly delivered ‘Covid-pod’. Huge hospital Covid signage was hastily erected. Doctors were redeployed to work in the Emergency Department from other specialties that were literally cancelled or scaled back hugely. I had one come to me at midnight asking why there were twice as many doctors in the place as patients; that he was bored and hadn’t seen a patient for three hours. Pre-lockdowns we were seeing over 300 patients each day. During the lockdown madness this dropped to less than 100 on some days. Many patients were petrified at the idea of coming to hospital. Others were instructed to stay away from the hospital unless extremely ill. This went on for months. Then the patients gradually came back, some with essentially no other access to healthcare. The department has not been quiet for some time now.

For many years now, my department (as with others throughout the U.K.) has been used as an overflow ward when beds cannot be found in the main hospital. Currently this is happening to an extent I have never previously experienced. A shortage of beds has been an issue for at least two of the three decades I have practised emergency medicine. It gets worse every year. The causes are multifactorial, but can be related to reduced numbers of beds or staff, decreasing access to community care, increasing waits for specialist referral and an elderly population whose primary (sometimes only) source of medical care is an emergency department. There is a major problem at the community discharge interface with patients waiting on packages of care, step-down wards, community beds and nursing homes. This exacerbates the bed cuts over the years and the centralisation of specialist services. I have heard of a hospital where one man will likely see his third Christmas as an inpatient. Patients are staying longer, and a lot are dying in hospital. These problems have just been exacerbated by ‘Covid Rules’, segregating the ‘Covid exposed’ from the ‘Covid recovered’ from the ‘Covid test positive’ from the ‘Covid test negative’ patients.

Emergency Department clinicians battle this with increasing frustration as the result is people essentially living in the department. Our department is back to seeing over 300 new patients per day and on one day last week we had over seventy patients living here awaiting hospital bed placement. Deaths in the department are increasing because sick people are remaining in the department for increasing lengths of time. The hardest bit is those needing end of life palliative care that get it delivered in the mayhem of an emergency department. It is very distressing for patients, staff and relatives.

Emergency departments operate as an outpatient interface between hospital and community. In the U.K., about the turn of the century (2000), most acute hospitals changed their admission arrangements from a GP referring to a specialty bed to a ‘single portal of entry’ arrangement. It was shrouded in the ‘safe and effective’ argument, but was a disaster on many levels. GPs no longer decided on admission; they decided on sending to the Emergency Department to decide on admission. The emergency departments were pulverised with a ‘four hour target’ for admission (under Blair’s Reforming Emergency Care). The media blamed emergency departments for ‘failing’ to meet the four hour target when, in effect, they were looking after the patients needing beds as well as serving emergencies.

The proper work of an emergency department is that of unscheduled care – people sourcing help in an emergency. The greater volume of work now is ‘processing’ admissions for inpatient specialties that don’t have beds for them. The Emergency Department is then expected to look after them, providing ward-level care (and sometimes intensive care) in corridors and rooms until a bed is available or they have been discharged (or left for heaven) from their Emergency Department trolley. (We have beds with hospital specialist mattresses for pressure sores in our corridors because of the long stays.)

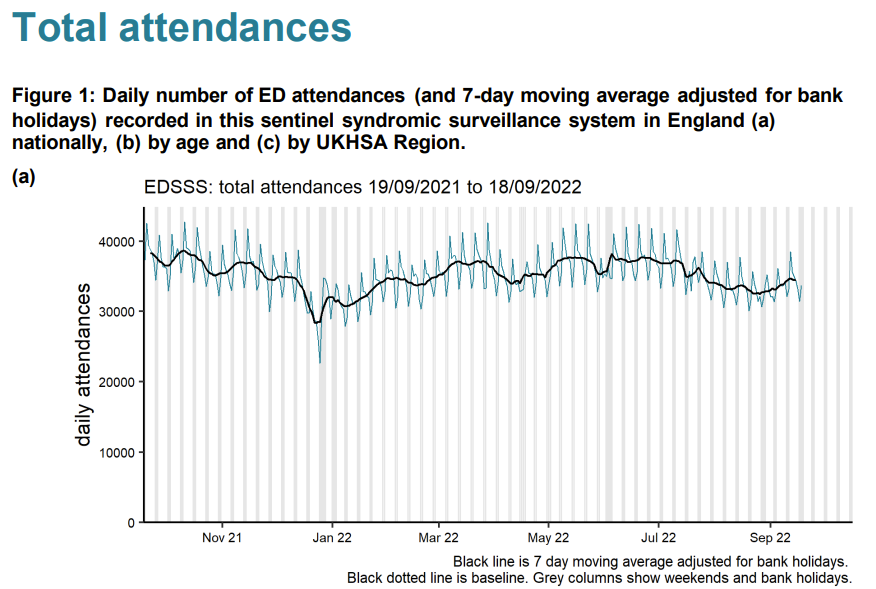

So, to say the numbers of admissions to emergency departments are lower than they were in the summer (as they currently are) gives no picture of the real congestion in emergency departments. You need to look at the number of patients waiting for beds. We are used to winter pressures with peaks and troughs. In 2021 we averaged 25 waiting in the department at a time (for at least a day) with no summer let-up. This year, for the same period, it is 45, with the worst summer ever. Emergency attendances are down – but admitted patients living in the department for days are more than doubled.

That aside, we have robust triage systems (stretched to the limit) where conditions that must be treated promptly are picked up within a target of 15 minutes of arrival (heart attacks, strokes, sepsis, haemorrhage etc.). The system is not perfect, but essentially these patients are identified as ‘time dependent conditions’ and brought to the Resuscitation Room for immediate assessment. Some are flagged by the Ambulance Service as ‘stand-by’ calls and sometimes paramedics take patients directly to where they can have, for example, urgent cardiology treatment to minimise damage from a heart attack. On the other hand, I am well aware of the recent problems with extensive delays in ambulance response times for some patients and occasions where the prioritisation has gone wrong.

Time-dependent conditions are being managed in the same way we always have and therefore perceived delays in managing them cannot be assumed to be contributing to the recent uptick in excess mortality. It is clear from experience that the incidences of heart attacks and strokes have increased significantly, although it will take time to demonstrate this with data.

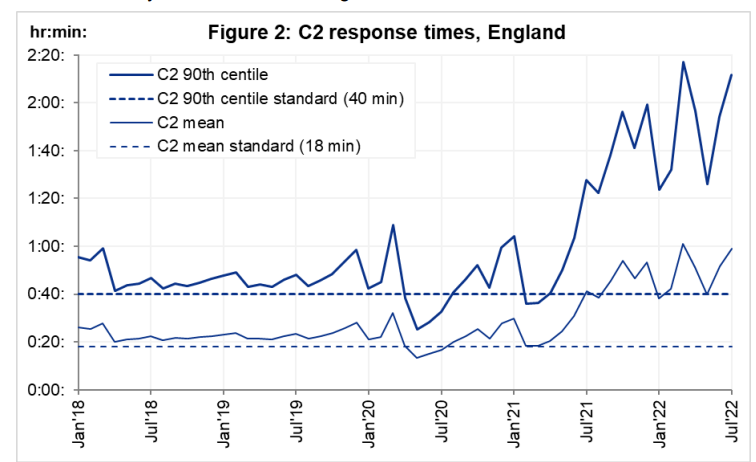

I have thought about what could be causing the excess mortality we have been seeing. With regard to ambulances in particular, there are many factors involved and it is difficult to quantify which is the greatest as the data are simply not available.

1. Ambulance staffing

Ambulance staffing has been an issue over the last two years. Paramedics have taken massive ‘Covid’ leave over the last couple years. As with hospital staff, any persistent cough (pre-testing), any positive test or even a contact with someone who had tested positive and you were expected to take 10-14 days off too. Any paramedic deemed ‘vulnerable’ would stay off too. The net effect of this was fewer paramedic ambulances on the road. We had private ‘ambulances’ including St. John and Red Cross supplementing patient hospital transport. That was a major factor, but is becoming less so now as there are fewer infections, and ‘Covid’ leave becomes sick leave again.

2. Hospital Chaos

A fear of accusations that hospitals had been responsible for spread of disease meant there were over-zealous systems of separation put in place. Patients were cohorted in the Emergency Department awaiting classification: PCR-positive, PCR-negative, Covid-recovered, Covid-exposed, clinical-Covid without a test result etc. These patients could only be admitted to a ward bed if there was one available in their category. This problem was compounded with ward beds being closed for ‘social distancing.’ Covid rules meant if a patient needed resuscitation it was done in the only (tiny) negative pressure room in the department.

Patients were kept in ambulances until a separate room in the Emergency Department could be found because the whole department became organised around one disease. It was not uncommon in certain trusts to have your first 24 hours of hospital treatment in the back of an ambulance. Some hospitals would not count the time in the ambulance as part of the patient’s hours in the department, meaning there was a perverse incentive to keep patients in ambulances.

3. Community Chaos

For those that haven’t noticed, for many, general practice now consists of a telephone triage service and a ‘vaccination’ service. For a lot of people that means their only source of healthcare is the Emergency Department and their only way of getting there is an ambulance. Where previously a nursing home may have had GP visits, now problems are dealt with by calling 999.

Despite this, there have been fewer patients overall attending the Emergency Department in 2022 than the equivalent period in 2021 (which was massively up on the empty departments of the lockdowns). Unfortunately, the patients are much sicker, older or simply can’t endure having formal investigation of a complex problem postponed further. Each of these patients requires more time and stays longer. We have the same amount of staff to deal with the 300 new presentations whether the department is empty or has over 70 living there. Our Emergency Department had it as a ‘never event’ to keep a patient in an ambulance, but recently we have been overruled by the pervasive ‘Infection Control’ who now dictate who can come in. An ambulance being used as a holding bay is an ambulance that can’t be turned around for another emergency.

Ambulance wait times started rising from July 2021. This was when ‘Freedom Day’ from the winter Covid restrictions finally arrived and at that point patients had had enough. There was a massive upswing of hospital presentations (accompanied by perhaps a little guilt at how the elderly had been managed) and in came the patients. A proportion of these patients were victims of having not had healthcare in lockdown. For example, I recently saw a patient who had a dangerously swollen abdominal aorta – an aneurysm – which had reached a size where surgery was needed to prevent rupture and death. Surgery was cancelled twice resulting in a re-attendance at my department after it catastrophically and fatally burst.

However, it has been many years since I have seen this number of patients with heart attacks and strokes. The timing of the uptick has coincided with the vaccination programmes. Correlation is not causation (unless it fits the narrative of course). Yesterday, I saw a superbly fit young man with no cardiovascular risk factors who had had two previous vaccinations. Despite healthy kidneys he had a cardiac cell death test result through the roof (troponin of over 800) after having chest pain while exercising. I worry that the spike protein or other factors have caused damage to the blood vessel lining cells such that exercise is precipitating spasm or rupture of plaques in coronary arteries leading to heart attacks. There are too many professional and amateur athletes now getting acute myocardial damage post-inoculation for it to be a complete coincidence. And it seems to be an effect unfortunately that can persist for many months after the injection. We are allowed to talk openly about the consequences of lockdown on health but not about potential consequences of the vaccines.

The pressures on emergency departments are therefore multifactorial. They stem from changes in how patients are referred to specialty care, the role departments have taken on as an overflow ward, and the additional constraints brought in with Covid rules. However, on top of these issues, the sicker patients we have seen, even in summer, have caused catastrophic pressure on the system. The knock-on effect is ambulances unable to drop off their patients and not being available for calls such that ambulance waiting times have rocketed. There is only so much we can do as emergency physicians. What is really needed is a sustainable fix for these underlying problems.