THE ROADMAP FOR THE 2025-2028 PANDEMIC ALREADY PUBLISHED BY EVENT 201 ORGANISERS

Sun 9:27 am +01:00, 25 Oct 2020

From the same notorious Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security who nailed the scenario of the current “pandemic” months before it happened during the “Event 201” simulation;

Ladies and gents, let us introduce you to SPARS, your next “invisible enemy”

EXCERPTS

Disclaimer

This is a hypothetical scenario designed to illustrate the public health risk communication challenges that could potentially emerge during a naturally occurring infectious disease outbreak requiring development and distribution of novel and/or investigational drugs, vaccines, therapeutics, or other medical countermeasures.

The infectious pathogen, medical countermeasures, characters, news media excerpts, social media posts, and government agency responses described herein are entirely fictional.

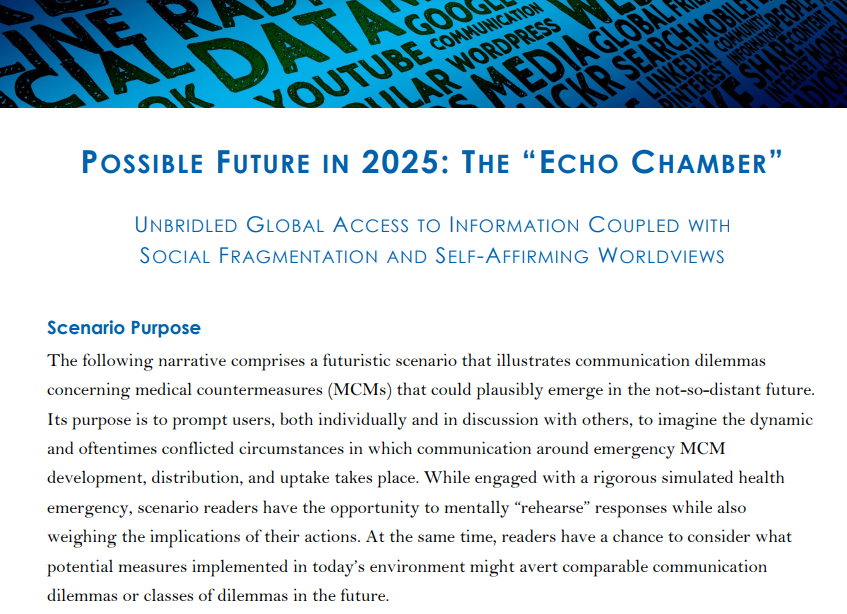

POSSIBLE FUTURE IN 2025:

THE “ECHO CHAMBER” – UNBRIDLED GLOBAL ACCESS TO INFORMATION COUPLED WITH SOCIAL FRAGMENTATION AND SELF-AFFIRMING WORLDVIEWS

Scenario Purpose

The following narrative comprises a futuristic scenario that illustrates communication dilemmas concerning medical countermeasures (MCMs) that could plausibly emerge in the not-so-distant future.

Its purpose is to prompt users, both individually and in discussion with others, to imagine the dynamic and oftentimes conflicted circumstances in which communication around emergency MCM development, distribution, and uptake takes place. While engaged with a rigorous simulated health emergency, scenario readers have the opportunity to mentally “rehearse” responses while also

weighing the implications of their actions. At the same time, readers have a chance to consider what potential measures implemented in today’s environment might avert comparable communication dilemmas or classes of dilemmas in the future.

Generation Purpose

This prospective scenario was developed through a combination of inductive and deductive approaches delineated by Ogilvy and Schwartz.

Scenario Environment

In the year 2025, the world has become simultaneously more connected, yet more divided. Nearly universal access to wireless internet and new technology—including internet accessing technology (IAT): thin, flexible screens that can be temporarily attached to briefcases, backpacks, or clothing and used to stream content from the internet—has provided the means for readily sharing news and

information. However, many have chosen to self-restrict the sources they turn to for information, often electing to interact only with those with whom they agree. This trend has increasingly isolated cliques from one another, making communication across and between these groups more and more difficult.

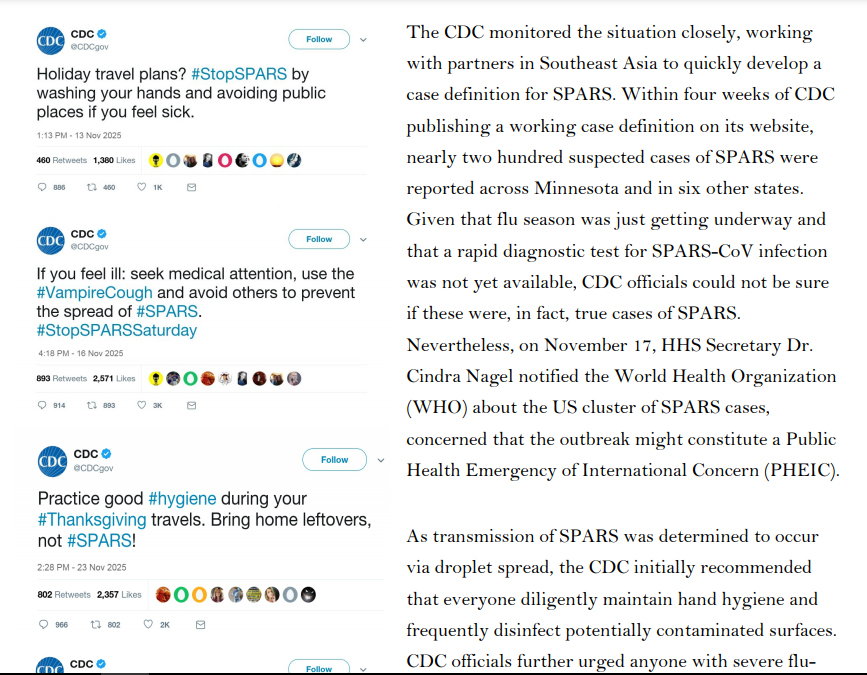

From a government standpoint, the current administration is led by President Randall Archer, who took office in January 2025. Archer served as Vice President under President Jaclyn Bennett (2020-2024), who did not seek a second term due to health concerns. The two remain close and Bennett acts as a close confidante and unofficial advisor to President Archer. The majority of President Archer’s

senior staff, including Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Dr. Cindra Nagel, are carryovers from Bennett’s administration. At the time of the initial SPARS outbreak Nagel has served in this position for just over three years.

In regards to MCM communication more specifically, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and other public health agencies have increasingly adopted a diverse range of social media technologies, including long-existing platforms such as Facebook, Snapchat, and Twitter, as well as emerging platforms like ZapQ, a platform that enables users to aggregate and archive selected media content from other platforms and communicate with cloud-based social groups based on common interests and current events. Federal and state public health organizations have also developed agency-specific applications and ramped up efforts to maintain and update agency websites.

Challenging their technological grip, however, are the diversity of new information and media platforms and the speed with which the social media community evolves. Moreover, while technologically savvy and capable, these agencies still lag in terms of their “multilingual” skills, cultural competence, and ability to be present on all forms of social media. Additionally, these agencies

face considerable budget constraints, which further complicate their efforts to expand their presence across the aforementioned platforms, increase social media literacy among their communication workforces, and improve public uptake of key messages.

THE SPARS OUTBREAK BEGINS

CHAPTER ONE

In mid-October 2025, three deaths were reported among members of the First Baptist Church of St. Paul, Minnesota. Two of the church members had recently returned from a missionary trip to the Philippines, where they provided relief to victims of regional floods. The third was the mother of a church member who had also traveled to the Philippines with the church group but who had been only

mildly sick himself. Based on the patients’ reported symptoms, healthcare providers initially guessed that they had died from seasonal influenza, which health officials predicted would be particularly virulent and widespread that fall. However, laboratory tests were negative for influenza. Unable to identify the causative agent, officials at the Minnesota Department of Health’s Public Health Laboratory sent the patients’ clinical specimens to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), where scientists confirmed that the patients did not have influenza. One CDC scientist recalled reading a recent ProMed dispatch describing the emergence of a novel coronavirus in Southeast Asia, and ran a

pancoronavirus RT-PCR test. A week later, the CDC team confirmed that the three patients were, in fact, infected with a novel coronavirus, which was dubbed the St. Paul Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SPARS-CoV, or SPARS), after the city where the first cluster of cases had been identified.

A POSSIBLE CURE

CHAPTER TWO

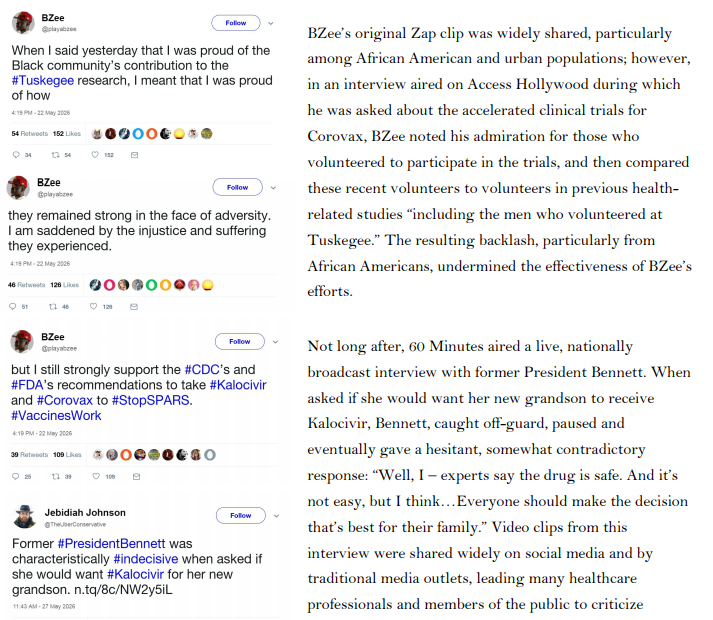

… By late December, public concern about SPARS in the United States was extremely high, and there was intense public pressure to identify

treatments for the disease.

At that time, no treatment or vaccine for SPARS was approved for use in humans. The antiviral Kalocivir, which was initially developed as a therapeutic for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), was one of several antiviral drugs authorized in the United States by the FDA to treat a handful of severe SPARS cases under its Expanded Access protocol. Kalocivir had shown some evidence of efficacy against other coronaviruses, and a small inventory of the drug was already a part of the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) in anticipation of FDA approval, despite some concerns about potential adverse side effects. The lack of concrete information regarding potential treatments in the face of the increasingly rapid spread of SPARS prompted demands from the media, the public, and political leaders for the FDA to be more

forthcoming with information on potential treatment options.

A POTENTIAL VACCINE

CHAPTER THREE

Shortly after authorizing expanded access to Kalocivir for select patients, the FDA received reports of an animal vaccine developed by GMI, a multinational livestock conglomerate operating cattle and pig farms in, among other places, Southeast Asia. Since 2021, ranchers had been using the vaccine to prevent a SPARS-like respiratory coronavirus disease in cows and pigs in the Philippines and other Southeast Asian countries. Data provided by GMI suggested that the vaccine was effective at preventing SPARS-like illnesses in cows, pigs, and other hooved mammals, but internal trials revealed several worrisome side effects, including swollen legs, severe joint pain, and encephalitis leading to seizures or death. Because any animals experiencing these side effects were immediately killed, and because animals were typically slaughtered within a year of vaccination, further information regarding the short- and long-term effects of the GMI vaccine was unavailable.

Lacking a viable alternative—and considering the potentially high morbidity and mortality associated with SPARS (at the time the case fatality rate was still considered to be 4.7%)—the United States government contacted GMI in regards to the vaccine. After laboratory tests confirmed that the coronavirus affecting livestock in Southeast Asia was closely related to SPARS-CoV, the US began an

extensive review of GMI’s animal vaccine development and testing processes. Shortly thereafter, federal health authorities awarded a contract to CynBio, a US-based pharmaceutical company, to develop a SPARS vaccine based on the GMI model. The contract included requirements for safety testing, ensuring the vaccine would be safe and effective for human use. It also provided considerable

funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and included provisions for priority review by the FDA. Additionally, HHS Secretary Nagel agreed in principle to invoke the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act (PREP Act), thereby providing liability protection for CynBio and future vaccine providers in the event that vaccine recipients experienced any adverse effects.

And so forth.

Unless we stop these psychos.

We are funded solely by our most generous readers and we want to keep this way. Help SILVIEW.media deliver more, better, faster, please donate here, anything helps. Thank you!

The roadmap for the 2025-2028 pandemic already published by Event 201 organisers