New CDC guidelines are aligned with science

Mon 9:14 am +01:00, 31 Aug 2020ANALYSIS

BY JENNIFER CABRERA

On August 24, the CDC updated its guidance on testing for SARS-CoV-2 to state that an individual who does not have COVID-19 symptoms and has not been in close contact with someone known to have a COVID-19 infection does not need a test. The guidance also states that individuals do not necessarily need a test if they’ve been in close contact (within 6 feet) of a person with a COVID-19 infection for at least 15 minutes but do not have symptoms. Testing is also not needed for individuals who are “in a high COVID-19 transmission area and attend a public or private gathering of more than 10 people (without widespread mask wearing or physical distancing).”

The intended use of PCR tests

COVID-19 tests are mainly rRT-PCR (real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction) tests, while a smaller number are antigen tests. All tests were approved under Emergency Use Authorizations, and information about their specificity and sensitivity is nearly impossible to find, even if you know which test a particular lab is using. The fact sheet for the Quest Diagnostics SARS-CoV-2 rRT-PCR test states, “This test is to be performed only using respiratory specimens collected from individuals suspected of COVID-19 by their healthcare provider.”

The fact sheet goes on to explain what it means if a specimen tests positive: “A positive test result for COVID-19 indicates that RNA from SARS-CoV-2 was detected, and the patient is infected with the virus and presumed to be contagious. Laboratory test results should always be considered in the context of clinical observations and epidemiological data in making a final diagnosis and patient management decisions.”

Needless to say, mass testing of asymptomatic individuals does not generally involve an examination by a healthcare provider to determine whether an individual is suspected of COVID-19 or to make a diagnosis from clinical observations.

False positives

All tests have false positives, but the number of false positives associated with the PCR tests currently in use is not well understood. False positives can arise from low sensitivity or specificity of the test, low prevalence in the community, or lab errors.

When tests have relatively low rates of false positives and the tests are used in conjunction with an examination by a healthcare professional, the false positive rate is less important, but when we’re doing well over half a million tests a day in the United States, the number of false positives can be large enough to obscure the actual prevalence of the virus.

To say a test is 90% sensitive means that it will correctly identify 90% of the people who are infected (i.e., correct positives). So if 10 infected people are tested, 9 of the tests will return positive results.

To say a test is 90% specific means that it will correctly identify 90% of people who are not infected with that specific virus (i.e., correct negatives). So if 10 healthy people are tested (or people with a different virus), 9 of the tests will return negative results.

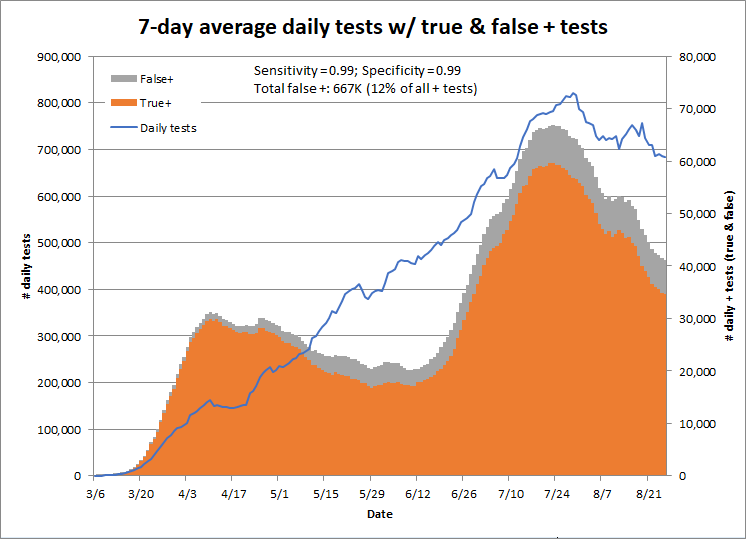

To explain how this works with COVID tests to date, if the test has 99% sensitivity and specificity, approximately 12%, or 667,000, of positive tests to date have been false positives. According to the Quest Diagnostics Fact Sheet referenced above, a false positive results in “a recommendation for isolation of the patient, monitoring of household or other close contacts for symptoms, patient isolation that might limit contact with family or friends and may increase contact with other potentially COVID-19 patients, limits in the ability to work, the delayed diagnosis and treatment for the true infection causing the symptoms, unnecessary prescription of a treatment or therapy, or other unintended adverse effects.”

It’s possible that this happens to more than 6,000 people every day in the United States under our current mass testing policies.

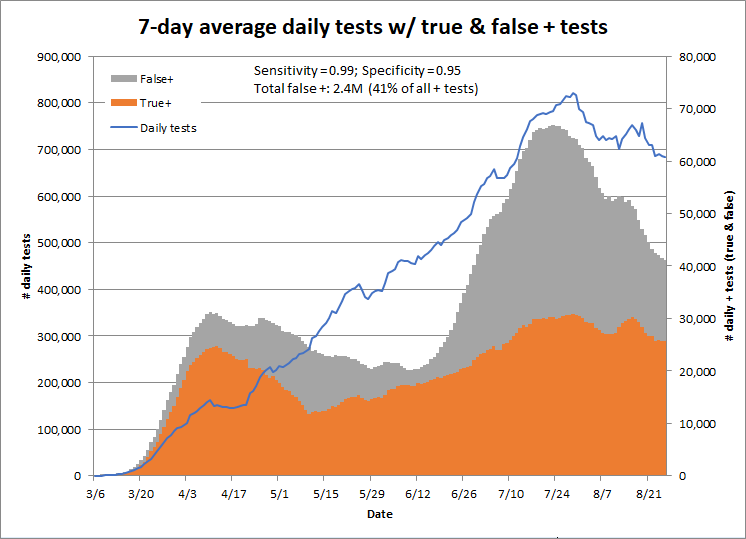

This graph shows the number of true and false positives by date if the tests are both 99% specific and sensitive.

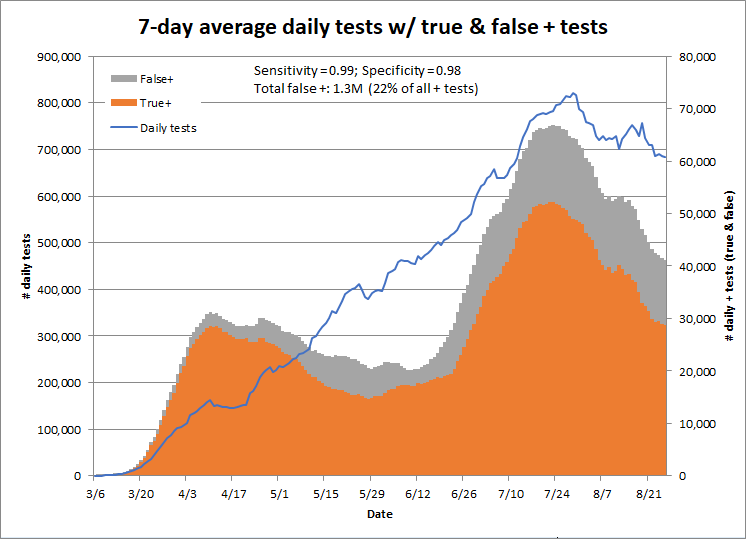

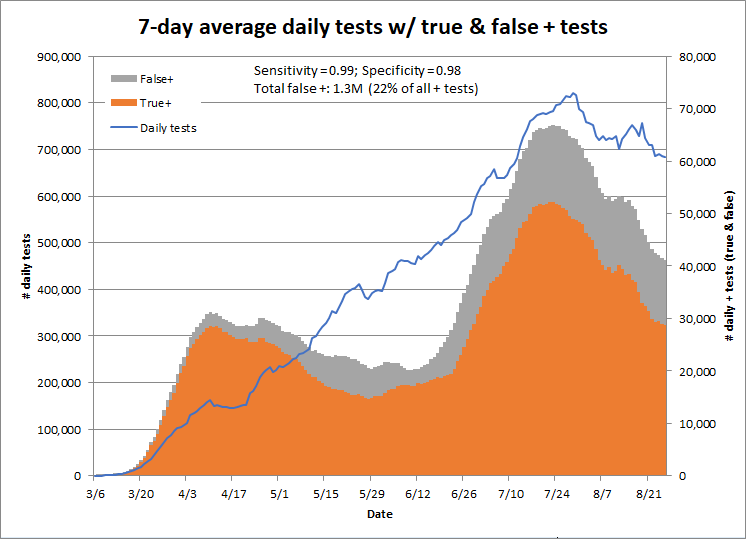

Changing the sensitivity doesn’t matter much, but even small changes in the specificity lead to large changes in the number of false positives. This chart shows the results for a test with 98% specificity and 99% sensitivity; this test would result in 1.3 million false positives to date, or 22% of all positive tests.

Using a specificity of 95% would result in 2.4 million false positives to date, or 41% of all positive tests. Clearly, we need more information about the actual specificity of the tests in use.

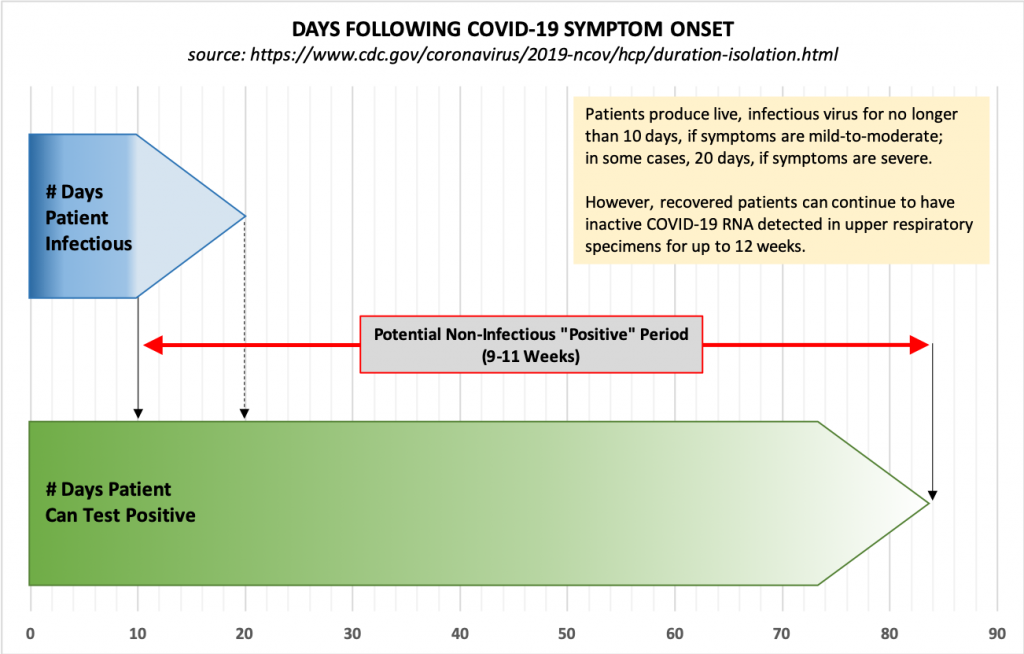

PCR tests detect inactive RNA

We also know now that individuals who become infected with COVID-19 and recover “can continue to have SARS-CoV-2 RNA detected in their upper respiratory specimens for up to 12 weeks.” This means that a test of an asymptomatic person may indicate infection long after a patient has recovered, and these positive tests are in addition to the false positives described above.

Because of this, the CDC no longer recommends testing to determine when a patient can leave isolation. Instead, “For most persons with COVID-19 illness, isolation and precautions can generally be discontinued 10 days after symptom onset and resolution of fever for at least 24 hours, without the use of fever-reducing medications, and with improvement of other symptoms.” Also, “For persons who never develop symptoms, isolation and other precautions can be discontinued 10 days after the date of their first positive RT-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 RNA.”

Mass testing of asymptomatic individuals is likely to generate positive tests for an unknown number of people who have had a mild or asymptomatic case and recovered. Isolation of these individuals provides no benefit to the community and has all of the downsides described above for false positives.

Weak asymptomatic transmission

Recently-published studies (Annals of Internal Medicine and Respir Med) indicate that household contact is the main setting for transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the risk for transmission increases with severity of the case, and “the infectivity of some asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 carriers might be weak.”

COVID-like illness (CLI) as a better indicator of prevalence

All regions in the United States track and report the number of emergency department visits for various sets of symptoms, including “Coronavirus like illness (CLI) or a COVID-19 diagnostic code,” “Influenza like illness (ILI without mention of specific influenza),” “Pneumonia,” and “Shortness of breath.” The CDC reports these by state here, with a few days’ delay. This information could be made available by county for monitoring of the prevalence of COVID-like illness in communities.

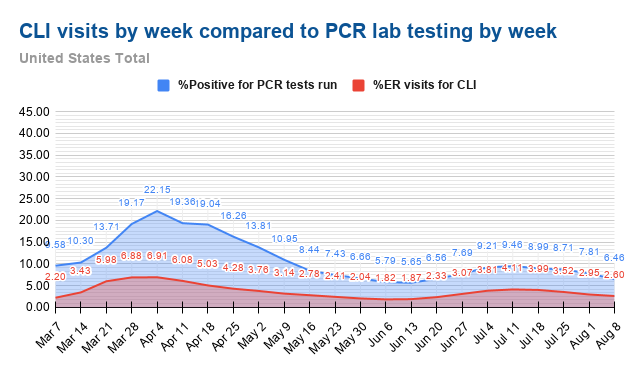

Kyle Lamb has posted charts comparing the percent of positive PCR tests and the percentage of emergency room visits for CLI, and they have the same shape, indicating that CLI is a good proxy for the prevalence of COVID in a community.

Mass testing has big drawbacks for individuals without adding useful information for the community

For all the reasons described above, mass testing of asymptomatic individuals is likely to produce large numbers of false positives, either from the inherent limitations of the test or from past infections.

The number or percentage of emergency room visits for COVID-like illness provides the indicator that public health officials need without testing individuals who are asymptomatic and thus likely to get false positives that limit their ability to go to work, attend school, and care for family members.

The new guidance from the CDC reflects our growing understanding of the unreliability of asymptomatic testing, the evidence that asymptomatic individuals are “weak” spreaders, and data showing that the number of emergency room visits for CLI are a good indicator of community prevalence without the downside of isolating individuals who are unlikely to spread COVID.

https://rationalground.com/new-cdc-guidelines-are-aligned-with-science/